John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune and his love for the world of flora

While residing at England, J. E. D. Bethune started taking keen interest on Indian education from the documents which reached him. He was convinced of the proficiency of the native students and the efforts of Government run institutions. Upon his arrival to India, Bethune started drawing attention of the Bengali men folk towards the necessity and benefit of women education. The refinement in taste of an educated woman was bound to enhance the quality of domestic life due to compatibility in intellectual capacity of the married couple. An educated mother plays pivotal role in shaping the intellect and moral faculties of her children during their formative years. Thus she lays a solid foundation in the character of the future citizens. The progress of a nation is largely the outcome of the degree to which the womenfolk exerted their refined mental influence on societal matters.1 Thus Bethune took upon himself to become instrumental in pioneering women education in India.

On 6th

November, 1876, at the occasion of acquisition of land jointly with Raja

Dakshinaranjan Mookherjee and laying the foundation stone of The Female School,

Bethune says “You have seen possession of this land symbolically given, by

delivering to us a young Asoka tree, which I hope that one of the ladies

present will presently do us the honour of planting in a conspicuous place, in

that which is intended to become the garden of the school. The choice of the

particular tree for that purpose has not been made unadvisedly, or without a

meaning. I am told that its Bengali name may not be unfitly paraphrased as “The

Tree of Gladness”. It is commended for this day’s ceremony not only by the

gracefulness of its foliage, and the surpassing beauty of its flowers, but also

because it is held in especial honour among Hindu women. I understand that

formerly they believed that by eating its blossoms, they should bring a

blessing on their children. It seemed to me therefore not an inappropriate

representation of an institution of the fruits of which they will indeed

consent to partake they will bring upon them the choicest blessings of which

our nature is capable.”1, 2 It was on this occasion that Bethune

declared that “the Asoka tree be made the symbol of female education in India,

and not only here but by every school which has been already established in the

villages round Calcutta in imitation of this, and near all those which shall

hereafter be multiplied in the land. I suggest that the Asoka tree be planted,

a new tree of liberty, to remind us of the bond of fellowship, which unites our

labours in one common sense.”1, 2 Today, the majestic tree stands

and the premises of Bethune College grandly displaying Bethune’s words on a

picturesque plaque.

The connection

between women and the Asoka tree (Saraca

asoka) can be traced back to Indian mythology where Goddess Sita after her abduction

chooses to stay in Asoka Vatika. The name translates to a-shoka meaning sorrow

less in vernacular language. Ayurveda prescribes bark of Asoka tree for

gynecological disorders by restoring

hormonal balance between estrogen and progesterone. Other beneficial roles

include curing of skin problems, helping in blood purification, lowering of

cholesterol and acting as cardiac tonic. The tall and conical ornamental tree

is also referred to as Asoka tree, but it is a different plant, Polialthia longifolia. In contrast the

medicinal Asoka tree has a broader canopy and orange flowers.3

Bethune’s interest

for floral nomenclature and documentation can be inferred upon from a few

evidences at hand. He observes that “European botanists have also selected this

tree to associate it with the memory of one whom England ever lent to India.

The Jonesia Asoka, for that is its botanical name recalls the name of the great

Sir William Jones one of the earliest who exerted himself to link together

learning of the East and the Western worlds, for his zealous untiring labours

in the universal spread of knowledge appeared to them to be fitly represented

by the elegant and exuberant beauty of this tree”.1, 2

From the Library

and Archives at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew a correspondence between Bethune and

Sir William Jackson Hooker; the then director, can be retrieved dating back to 8th

February 1850. Bethune was keen in publishing the specimen maps of Berghaus' plant

geography in England and took upon himself the financial responsibility

collecting funds along with Mr. Hodgson and Sir James Colvile. At that time

Bethune was the president of The Calcutta School Book Society. He believed that

undertaking the publication of this important document in England would enhance

sale due to being associated with persons of repute such as Berghaus and

Humboldt. He further stated that the Indian copyright of the work be given to

himself, in trust for the Calcutta School Book Society. The English copyright

would belong to Hooker. In another correspondence dated 2nd June

1851 from Darjeeling, Hooper writes to Bethune that the work on Berghaus'

geography has been withheld as the later has not provided relevant information.

However, Bethune recollected that he had sent the botanical illustrations

(probably engraved on steel plates) to London by Captain Cavanagh, who

accompanied the Nipâl Ambassador addressing it either directly to Hooker or to

his brother Captain Bethune.4, 5. Bethune was amongst the few who

sought for the cultivation of the Indian mind by the light of education. He

believed that scholastic pursuits prepare one for life by inculcating practical

wisdom. His inclination towards

different branches of knowledge ranging from mathematics, metaphysics,

astronomy, logic, natural philosophy, foreign and vernacular languages stems

from his belief that “the attention of the learner shall be fixed exclusively

or almost exclusively on the truth taught, and little or not at all on the form

of the vehicle through which it is conveyed.”6

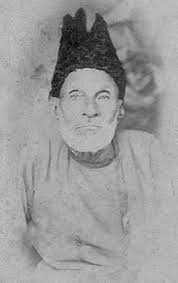

Sir J. E. D. Bethune

Plaque at the Ashoka tree decorated on Bethune Day

References:

1 Bethune Commemorative

Volume 1976

2 The Bengal

Harkara and the Indian Gazette 9th November 1850

3 https://tdu.edu.in/ashoka-tree/

4 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heinrich_Berghaus

5 https://plants.jstor.org/stable/10.5555/al.ap.visual.kdcas424

6 Address at

Kisnagaur. General Report on Public Instruction, in the lower provinces of the

Bengal Presidency from1st October1850 to 30th September 1851.

Calcutta: F. Carberry, Bengal Militant Orphan Press. 1852.

Comments

Post a Comment